"The Masque of the Red Death," originally published as "The Mask of the Red Death" (1842), is a short story by Edgar Allan Poe. The story follows Prince Prospero's attempts to avoid a dangerous plague known as the Red Death by hiding in his abbey. He, along with many other wealthy nobles, has a masquerade ball within seven rooms of his abbey, each decorated with a different color. In the midst of their revelry, a mysterious figure enters and makes his way through each of the rooms. Prospero dies after confronting this stranger. The story follows many traditions of Gothic fiction and is often analyzed as an allegory about the inevitability of death, though some critics advise against an allegorical reading. Many different interpretations have been presented, as well as attempts to identify the true nature of the titular disease.

The story was first published in May 1842 in Graham's Magazine. It has since been adapted in many different forms, including the 1964 film starring Vincent Price. It has been alluded to by other works in many types of media.

Plot summary

The story takes place at the castellated abbey of the "happy and dauntless and sagacious" Prince Prospero. Prospero and one thousand other nobles have taken refuge in this walled abbey to escape the Red Death, a terrible plague that has swept over the land. The symptoms of the Red Death are gruesome: The victim is overcome by convulsive agony and sweats blood instead of water. The plague is said to kill within half an hour. Prospero and his court are presented as indifferent to the sufferings of the population at large, intending to await the end of the plague in luxury and safety behind the walls of their secure refuge, having welded the doors shut.

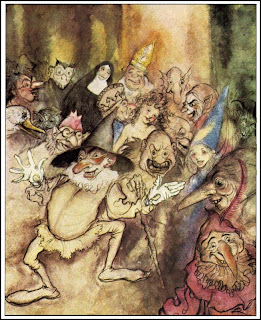

One night, Prospero holds a masquerade ball to entertain his guests in seven colored rooms of the abbey. Six of the rooms are each decorated and illuminated in a specific color: Blue, purple, green, orange, white, and violet. The last room is decorated in black and is illuminated by a blood-red light; because of this chilling pair of colors, few guests are brave enough to venture into the seventh room. The room is also the location of a large ebony clock that ominously clangs at each hour, upon which everyone stops talking and the orchestra stops playing. At the chiming of midnight, Prospero notices one figure in a dark, blood-spattered robe resembling a funeral shroud, with an extremely lifelike mask resembling a stiffened corpse, and with the traits of the Red Death, which all at the ball have been desperate to escape. Gravely insulted, Prospero demands to know the identity of the mysterious guest so that they can hang him. When none dares to approach the figure, instead letting him pass through the seven chambers, the prince pursues him with a drawn dagger until he is cornered in the seventh room, the black room with the scarlet-tinted windows. When the figure turns to face him, the Prince falls dead. The enraged and terrified revelers surge into the black room and remove the mask, only to find that there is no face underneath it. Only then do they realize that the figure is the Red Death itself, and all of the guests contract and succumb to the disease. The final line of the story sums up: "And Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all."

Analysis

In "The Masque of the Red Death" Poe adopts many conventions of traditional Gothic fiction, including the setting of a castle. The multiple single-toned rooms may be representative of the human mind, showing different personality types. The imagery of blood and time throughout also indicate corporeality. The plague may, in fact, represent typical attributes of human life and mortality.[1] This would imply the entire story is an allegory about man's futile attempts to stave off death; this interpretation is commonly accepted.[2] However, there is much dispute over how to interpret "The Masque of the Red Death"; some suggest it is not allegorical, especially due to Poe's admission of a distaste for didacticism in literature.[3] If the story really does have a moral, Poe does not explicitly state that moral in the text.[4]

Blood, emphasized throughout the tale along with the color red, serves as a dual symbol, representing both death and life. This is emphasized by the masked figure – never explicitly stated to be the Red Death, but only a reveler in a costume of the Red Death – making his initial appearance in the easternmost room, which is colored blue, a color most often associated with birth.[5]

Though Prospero's castle is meant to keep the sickness out, it is ultimately an oppressive structure. Its maze-like design and tall and narrow windows become almost burlesque in the final black room, so oppressive that "there were few of the company bold enough to set foot within its precincts at all."[6] Additionally, the castle is meant to be a closed space, but the stranger is still able to get in, suggesting that control is an illusion.[7]

Like many of Poe's tales, "The Masque of the Red Death" has also been interpreted autobiographically. In this point of view, Prince Prospero is Poe as a wealthy young man, part of a distinguished family much like Poe's foster parents, the Allans. Under this interpretation, Poe is seeking refuge from the dangers of the outside world, and his portrayal of himself as the only person willing to confront the stranger is emblematic of Poe's rush towards inescapable dangers in his own life.[8]

The "Red Death"

The disease the Red Death is fictitious. Poe describes it as causing "sharp pains, and sudden dizziness, and then profuse bleeding at the pores" leading to death within half an hour.

It is likely that the disease was inspired by tuberculosis (or consumption, as it was known then), since Poe's wife Virginia was suffering from the disease at the time the story was written. Like the character of Prince Prospero, Poe tried to ignore the fatality of the disease.[9] Poe's mother Eliza, brother William, and foster mother Frances Allan had also died of tuberculosis. Alternatively, the Red Death may refer to cholera; Poe would have witnessed an epidemic of cholera in Baltimore, Maryland in 1831.[10] Others have suggested that the plague is actually Bubonic plague or the Black death, emphasized by the climax of the story featuring the "Red" Death in the "black" room.[11] One writer likens the description to that of a viral hemorrhagic fever or necrotizing fasciitis.[12] It has been suggested that the Red Death is not a disease or sickness at all but something else[clarification needed] that is shared by all of humankind inherently.[13]

Publication history

Poe first published the story in the May 1842 edition of Graham's Lady's and Gentleman's Magazine as "The Mask of the Red Death," with the tagline "A Fantasy." This first publication earned him $12.[14] A revised version was published in the July 19, 1845 edition of the Broadway Journal under the now-standard title "The Masque of the Red Death."[15] The original title emphasized the figure at the end of the story; the new title puts emphasis on the masquerade ball.[16]

Film, TV, theatrical, or radio adaptations

The story inspired Russian filmmaker Vladimir Gardin's A Spectre Haunts Europe in 1921.

Basil Rathbone read the entire short story in his early 1960s Cademon LP recording The Tales of Edgar Allan Poe. Other audiobook recordings have had Christopher Lee, Hurd Hatfield, Martin Donegan and Gabriel Byrne as readers.

Short films based on the story include a 1969 Zagreb Film production, Maska crvene smrti, and [17] a 2006 Tarantula production directed by Jacques Donjean, Le Masque de la Mort rouge.[18]

The story was adapted in 1964 by Roger Corman as a film, The Masque of the Red Death, starring Vincent Price. The film also adapted parts of another Poe story, "Hop-Frog", involving the court jester and his wife. Corman produced, but did not direct, a remake of the film in 1989, starring Adrian Paul as Prince Prospero.[19]

The story was adapted, combined with elements from Poe's "The Cask of Amontillado," by American director Orson Welles as a planned episode for the Poe anthology film Spirits of the Dead, which was to have starred Welles as Prince Prospero and Oja Kodar as Fortunata. The French producers replaced the episode with segments directed by Roger Vadim and Louis Malle.

The story was adapted by George Lowther for the January 10, 1975, broadcast of the CBS Radio Mystery Theater. It starred Karl Swenson and Staats Cotsworth.

A radio reading was performed by Winifred Phillips, with music she composed. The program was produced by Winnie Waldron as part of National Public Radio's Tales by American Masters series.

The story has been adapted by Punchdrunk Productions, in collaboration with Battersea Arts Centre, as a promenade theatre performance in Battersea from September 17, 2007 to April 12, 2008.[20]

Musical adaptations and references

The heavy metal band Crimson Glory wrote and released the song "Masque of the Red Death", which follows the story, on their 1988 album Transcendence.

The horror adventure game The Dark Eye features a reading of the story by writer William S. Burroughs.

The metal band Stormwitch released the song "Masque Of The Red Death" on their 1985 album Tales Of Terror. Its lyrics follow the storyline.

The post-hardcore band Thrice effectively re-tells the story in the song "The Red Death", on their album The Illusion of Safety.

The Red Death is a metal band from Upstate New York whose name is derived from the title disease and released albums on Metal Blade Records and Siege of Amida/Ferret Records.

References

1.^ Fisher, Benjamin Franklin. "Poe and the Gothic tradition" as collected in The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe, edited by Kevin J. Hayes. New York City: Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0521797276 p. 88

2.^ Roppolo, Joseph Patrick. "Meaning and 'The Masque of the Red Death'", collected in Poe: A Collection of Critical Essays, edited by Robert Regan. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1967. p. 137

3.^ Roppolo, Joseph Patrick. "Meaning and 'The Masque of the Red Death'", collected in Poe: A Collection of Critical Essays, edited by Robert Regan. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1967. p. 134

4.^ Quinn, Arthur Hobson. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998. ISBN 0801857309. p. 331.

5.^ Roppolo, Joseph Patrick. "Meaning and 'The Masque of the Red Death'", collected in Poe: A Collection of Critical Essays, edited by Robert Regan. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1967. p. 141

6.^ Laurent, Sabrina. "Metaphor and Symbolism in The Masque of the Red Death", from Boheme: An Online Magazine of the Arts, Literature, and Subversion. July 2003. Available online.

7.^ Peeples, Scott. "Poe's 'constructiveness' and 'The Fall of the House of Usher'" as collected in The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe. Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0521797276 p. 186

8.^ Rein, David M. Edgar A. Poe: The Inner Pattern. New York: Philosophical Library, 1960. p. 33

9.^ Silverman, Kenneth. Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. Harper Perennial, 1991. ISBN 0060923318 p. 180-1

10.^ Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. Cooper Square Press, 1992. ISBN 0815410387 p. 133

11.^ Cummings Study Guide for "The Masque of the Red Death"

12.^ "Molecules of Death" 2nd edition, edited by R H Waring, G B Steventon, S C Mitchell. London: Imperial College Press, 2007

13.^ Roppolo, Joseph Patrick. "Meaning and 'The Masque of the Red Death'", collected in Poe: A Collection of Critical Essays, edited by Robert Regan. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1967. p. 139-40

14.^ Ostram, John Ward. "Poe's Literary Labors and Rewards" in Myths and Reality: The Mysterious Mr. Poe. Baltimore: The Edgar Allan Poe Society, 1987. p. 39

15.^ Edgar Allan Poe — "The Masque of the Red Death" at the Edgar Allan Poe Society online

16.^ Sova, Dawn B. Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z. New York: Checkmark Books, 2001. p. 149. ISBN 081604161X

17.^ "The Best of Zagreb Film Volume 1". Rembrandt Films.

18.^ "Le Masque de la Mort rouge de Jacques Donjean". Suivez mon regard.

19.^ Sova, Dawn B. Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z. New York: Checkmark Books, 2001. p. 150. ISBN 081604161X

20.^ National Theatre online

No comments:

Post a Comment