K-11 is an upcoming drama film directed by Jules Mann-Stewart and written by Jared Kurt, starring Kristen Stewart, and Nikki Reed as male characters. The film is due for release in 2010.

Plot

A man (Jason Mewes) wakes up, not knowing where he is and later finds it's a lesser known dormitory named "K11" that is a "world in itself" located in the Los Angeles county jail that mainly consists of people who may be a danger to themselves and to others in society, "eccentric, crazy" celebrities, homosexuals, cross dressers and child abusers. The man attempts to achieve a role in the dorm's hierarchy.

Production

The film is directed by Kristen Stewart's mother, Jules Mann-Stewart and is aiming for a 2010 release.

Casting

Kristen Stewart portrays a male to female transsexual prisoner with autism named Butterfly. Nikki Reed also portrays a prisoner who is transgender (previously a woman) and is a meth addicted prostitute named Mousey. Stewart and Reed had previously starred together in the Twilight film series. Jason Mewes will also star.

Jules-Mann Stewart

Johann Ludwig Tieck (May 31, 1773 – April 28, 1853) was a German poet, translator, editor, novelist, writer of Novellen, and critic, who was one of the founding fathers of the Romantic movement of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Early life

Tieck was born in Berlin, the son of a rope-maker. He was educated at the Friedrich-Werdersche Gymnasium, and at the universities of Halle, Göttingen and Erlangen. At Göttingen, he studied Shakespeare and the Elizabethan drama.

In 1794 he returned to Berlin, and attempted to make a living by writing. He contributed a number of short stories (1795–1798) to the series of Straussfedern, published by the bookseller C. F. Nicolai and originally edited by J. K. A. Musäus, and wrote Abdallah (1796) and a novel in letters, William Lovell (3 vols. 1795–1796).

Adoption of Romanticism

Tieck's transition to Romanticism is seen in the series of plays and stories published under the title Volksmärchen von Peter Lebrecht (3 vols., 1797), a collection which contains the admirable fairy-tale Der blonde Eckbert, which seamlessly blends exploration of the paranoiac mind with the realm of the supernatural, and the witty dramatic satire on Berlin literary taste, Der gestiefelte Kater. With his school and college friend Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder (1773–1798), he planned the novel Franz Sternbalds Wanderungen (vols. i–ii. 1798), which, with Wackenroder's Herzensergiessungen (1798), was the first expression of the romantic enthusiasm for old German art.

In 1798 Tieck married and in the following year settled in Jena, where he, the two brothers August and Friedrich Schlegel and Novalis were the leaders of the new Romantic school. His writings between 1798 and 1804 include the satirical drama, Prinz Zerbino (1799), and Romantische Dichtungen (2 vols., 1799-1800). The latter contains Tieck's most ambitious dramatic poems, Leben und Tod der heiligen Genoveva, Leben und Tod des kleinen Rotkäppchens, which were followed in 1804 by the remarkable "comedy" in two parts, Kaiser Oktavianus. These dramas, in which Tieck's poetic powers are to be seen at their best, are typical plays of the first Romantic school; although formless, and destitute of dramatic qualities, they show the influence of both Calderón and Shakespeare. Kaiser Oktavianus is a poetic glorification of the Middle Ages.

In 1801 Tieck went to Dresden, then lived for a time at Ziebingen near Frankfurt (Oder), and spent many months in Italy. In 1803 he published a translation of Minnelieder aus der schwäbischen Vorzeit, between 1799 and 1804 an excellent version of Don Quixote, and in 1811 two volumes of Elizabethan dramas, Altenglisches Theater. From 1812 to 1817 he collected in three volumes a number of his earlier stories and dramas, under the title Phantasus. In this collection appeared the stories Der Runenberg, Die Elfen, Der Pokal, and the dramatic fairy tale, Fortunat.

In 1817 Tieck visited England in order to collect materials for a work on Shakespeare (unfortunately never finished) and in 1819 he settled permanently in Dresden; from 1825 on he was literary adviser to the Court Theatre, and his semi-public readings from the dramatic poets gave him a reputation which extended far beyond the Saxon capital. The new series of short stories which he began to publish in 1822 also won him a wide popularity. Notable among these are Die Gemälde, Die Reisenden, Die Verlobung, and Des Lebens Überfluss.

More ambitious and on a wider canvas are the historical or semi-historical novels, Dichterleben (1826), Der Aufruhr in den Cevennen (1826, unfinished), Der Tod des Dichters (1834); Der junge Tischlermeister (1836; but begun in 1811) is an excellent story written under the influence of Goethe's Wilhelm Meister; Vittoria Accorombona (1840), the story of Vittoria Accoramboni written in the style of the French Romanticists, shows a falling-off.

Later years

In later years Tieck carried on a varied literary activity as critic (Dramaturgische Blätter, 2 vols., 1825–1826; Kritische Schriften, 2 vols., 1848); he also edited the translation of Shakespeare by August Wilhelm Schlegel, who was assisted by Tieck's daughter Dorothea (1790–1841) and by Wolf Heinrich, Graf von Baudissin (1789–1878); Shakespeares Vorschule (2 vols., 1823–1829); the works of Heinrich von Kleist (1826) and of Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz (1828). In 1841 Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia invited him to Berlin where he enjoyed a pension for his remaining years. He died on 28 April 1853.

Literary significance

Tieck's importance lay in the readiness with which he adapted himself to the emerging new ideas which arose at the close of the 18th century, as well as being a trailblazer in his own right with Romantic works such as der blonde Eckbert. His importance in German poetry, however, is restricted to his early period. In later years it was as the helpful friend and adviser of others, or as the well-read critic of wide sympathies, that Tieck distinguished himself.

Tieck also influenced Richard Wagner's Tannhäuser. It was from Phantasus that Wagner based the idea of Tannhäuser going to see the pope and Elisabeth dying in the song battle.

Works

Tieck's Schriften appeared in twenty vols. (1828–1846), and his Gesammelte Novellen in twelve (1852–1854). Nachgelassene Schriften were published in two vols. in 1855. There are several editions of Ausgewählte Werke by H. Welti (8 vols., 1886–1888); by J. Minor (in Kirschner's Deutsche Nationalliteratur, 144, 2 vols., 1885); by G. Klee (with an excellent biography, 3 vols., 1892), and G. Witkowski (4 vols., 1903) and Marianne Thalmann (4 vols., 1963–66).

Translations

The Elves and The Goblet was translated by Carlyle in German Romance (1827), The Pictures and The Betrothal by Bishop Thirlwall (1825). A translation of Vittoria Accorombona was published in 1845. A translation of Des Lebens Überfluss (Life's Luxuries, by E. N. Bennett) appeared in German Short Stories in the Oxford University Press World's Classics series in 1934, but the wit of the original comes over more strongly in The Superfluities of Life. A Tale Abridged from Tieck, which appeared anonymously in Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine in February 1845.The journey into the blue distance (Shirley) "The Romance of Little Red Riding Hood" (1801) was translated by Jack Zipes and included in his book "The Trials and Tribulations of Little Red Riding Hood."

Letters

Tieck's Letters have been published at various locations:

Ludwig Tieck und die Brüder Schlegel. Briefe ed. by Edgar Lohner (München 1972)

Briefe an Tieck were published in 4 vols. by K. von Holtei in 1864.

See also

Mozart's Berlin journey - Tieck's encounter with Mozart as an adolescent

Blond Eckbert - Judith Weir's operatic adaption of Tieck's novella der blonde Eckbert.

Bibliography

R. Köpke, Ludwig Tieck (2 vols., 1855) Tieck's earlier life.

H. von Friesen, Ludwig Tieck: Erinnerungen (2 vols., 1871) Dresden period.

A. Stern, Ludwig Tieck in Dresden (Zur Literatur der Gegenwart, 1879)

J. Minor, Tieck als Novellendichter (1884)

B. Steiner, L. Tieck und die Volksbücher (1893)

H. Bischof, Tieck als Dramaturg (1897)

W. Miessner, Tiecks Lyrik (1902)

Roger Paulin: Ludwig Tieck, 1985 (German) (Slg. Metzler M 185, 1987; German translation, 1988)

Kertz-Welzel, Alexandra. Die Transzendenz der Gefühle. Beziehungen zwischen Musik und Gefühl bei Wackenroder/Tieck und die Musikästhetik der Romantik. Saarbrücker Beiträge zur Literaturwissenschaft, no. 71. Ph.D. Dissertation (Saarbrücken, Germany: Universität des Saarlandes, 2000). St. Ingbert, Germany: Röhrig Universitätsverlag, 2001. ISBN 3-86110-278-1.

Welcome to the Rileys is an upcoming American independent drama film directed by Jake Scott, written by Ken Hixon, and starring Kristen Stewart, James Gandolfini and Melissa Leo. The film debuted at the 2010 Sundance Film Festival.

Plot

Since the death of his daughter, Doug Riley (James Gandolfini) begins to commit adultery with a waitress named Vivian, while his wife Lois (Melissa Leo) withholds a secret about their daughter Emily's death. From this guilt, she never ventures outside her house. When Vivian dies, Doug is devastated. In New Orleans' French Quarter, Doug finds himself in a strip club when he meets a sixteen year old prostitute named Mallory (Kristen Stewart). Doug calls Lois to inform her he will not be returning home. Lois finally leaves her house to reunite with Doug. When she arrives, she is horrified, but is also taken by Mallory's unusual resemblance to Emily. Lois precedes to move in. But Mallory does not wish to give up her life as a prostitute.

Sex is a 1926 play, written by, and starring, Mae West. It was very popular for about a year before the New York Police Department raided West and her company, charging them with obscenity, despite the fact that 325,000 people had watched it, including members of the police department and their wives, judges of the criminal courts, and seven members of the district attorney’s staff.

West was sentenced to 10 days in jail, getting out two days early for good behavior. The resulting publicity increased her national renown.

References

Theatre History: APRIL 26, By Anne Bradley and Ernio Hernandez, Playbill, on 26 Apr 2005

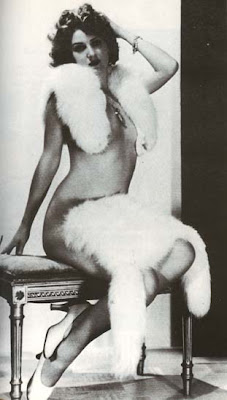

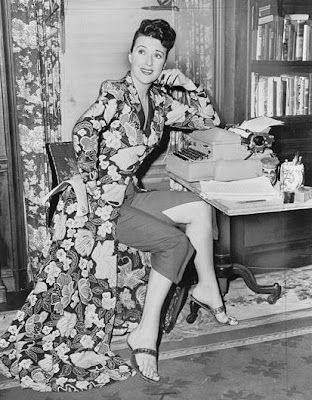

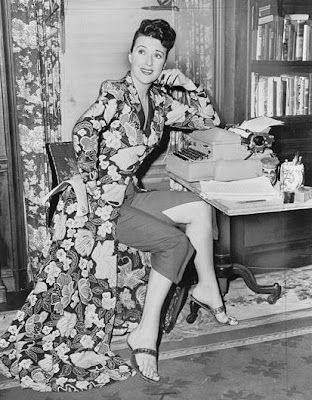

Gypsy Rose Lee (born January 8, 1911 – April 26, 1970) was an American burlesque entertainer, famous for her striptease act. She was also an actress and writer, whose 1957 memoir, written as a monument to her mother, was made into the stage musical and film Gypsy.

Gypsy was born Rose Louise Hovick in Seattle, Washington in 1911, although her mother later shaved three years off both of her daughters' ages. She was initially known by her middle name, Louise. Her mother, Rose Thompson Hovick, married John Olaf Hovick, who was a newspaper advertising salesman. Her sister, Ellen June Hovick (better known as actress June Havoc), was born in 1913.

After their parents divorced, the girls earned the family's money by appearing in vaudeville where June's talent shone, while Louise remained in the background. At the age of 13, June married a boy in the act named Bobby Reed. June left the act and went on to a brief career in marathon dancing before giving birth to April Reed around 1930.

Louise's singing and dancing talents were insufficient to sustain the act without June. Eventually, it became apparent that Louise could make money in burlesque, which earned her legendary status. Her innovations were an almost casual strip style, compared to the herky-jerky styles of most burlesque strippers (she emphasized the "tease" in "striptease") and she brought a sharp sense of humor into her act as well. She became as famous for her onstage wit as for her strip style, and—changing her stage name to Gypsy Rose Lee—she became one of the biggest stars of Minsky's Burlesque, where she performed for four years. She was frequently arrested in raids on the Minsky brothers' shows.

She eventually traveled to Hollywood, where she was billed as Louise Hovick. Her acting was generally panned, so she returned to New York City and invested in film producer Michael Todd. She eventually appeared as an actress in many of his films.

Trying to describe what Gypsy was (a "high-class" stripper), H. L. Mencken coined the term ecdysiast. Her style of intellectual recitation while stripping was spoofed in the number "Zip!" from Rodgers and Hart's Pal Joey, a play in which her sister June appeared. Gypsy can be seen performing an abbreviated version of her act (intellectual recitation and all) in the 1943 film Stage Door Canteen.

In 1941, Gypsy Rose Lee authored a mystery thriller called The G-String Murders which was made into the 1943 film Lady of Burlesque starring Barbara Stanwyck. While some assert this was in fact ghost-written by Craig Rice, there are also those who suggest that there is more than sufficient written evidence in the form of manuscripts and Lee's own correspondence to prove she wrote a large part of the novel herself under the guidance of Rice and others, including her friend and mentor, the editor George Davis. Lee's second murder mystery, Mother Finds a Body, was published in 1942.

Nicolas Jacques Pelletier was a French highwayman who was the first person to be executed by means of the guillotine on April 25, 1792.

The robbery and subsequent sentencing

Pelletier routinely associated with a group of known criminals. On the night of 14 October 1791, with several unknown accomplices, he attacked a passerby in the rue Bourbon-Villeneuve in Paris and stole his wallet and several securities. During the robbery he also killed the man, though this is disputed in later literature as possibly just having been an assault and robbery or also an assault, robbery, and rape. He was apprehended and accused that same night, for the cries for help alerted the city, and a nearby guard arrested Pelletier. Judge Jacob Augustin Moreau, the District Judge of Sens, was to hear the case. A legal advisor was given to Pelletier, but despite repeated calls for a fairer court hearing, the judge ordered a death sentence for 31 December 1791. On 24 December 1791, the Second Criminal Court confirmed Judge Moreau's sentence. The execution was stayed, however, after the National Assembly made decapitation the only legal method of capital punishment. Pelletier waited in jail for more than three months as the guillotine was built in Strasbourg under the direction of the surgeon Antoine Louison, at a cost of thirty-eight livres. Meanwhile, the public executioner Charles Henri Sanson, tested the machine on corpses in the Bicêtre Hospital. Sanson preferred the guillotine over the former decapitation by sword, as the latter reminded him of the nobility's former privileges that the Revolution had worked to eliminate. On 24 January 1792, a Third Criminal Court confirmed the execution.

The execution was delayed due to the ongoing debate on the legal method of execution. Finally, the National Assembly decreed on 23 March 1792 in favor of the guillotine.

Execution day

The guillotine was placed on top of a scaffolding outside the Hôtel de Ville in the Place de Grève, where public executions had been held under the reign of King Louis XV. Pierre Louis Roederer, thinking that a large number of people would come to see the first-ever public execution-by-guillotine, thought that there might be difficulty in preserving order. He wrote to General Lafayette to ask for National Guardsmen to make sure the event went smoothly.

The execution took place at 3:30 in the afternoon. Pelletier was led to the scaffolding wearing a red shirt. The large crowd predicted by Roederer was already there waiting, eager to see the novel invention at work. The guillotine, which was also red in color, had been previously fully prepared, and Sanson moved quickly. Within seconds, the guillotine and Pelletier were positioned correctly, and Pelletier was instantly decapitated.

The crowd, however, was dissatisfied with the guillotine. They felt it was too swift and "clinically effective" to provide proper entertainment, as compared to previous execution methods, such as hanging, death-by-sword, or breaking at the wheel. The public even called out, "Bring back our wooden gallows!"

Afterwards

Pelletier was only the first person to be executed by guillotine. After the establishment of the Revolutionary Tribunal on 10 August, the guillotine moved to the Tuileries Palace. Executions were held either at the Place du Carrousel before the palace or the Place de la Révolution beyond its garden. The Revolutionary Tribunal executed just 28 people; the vast majority were for violent crimes like Pelletier's, unlike the subsequent Reign of Terror.[16]

References

1.^ "Crime Library". National Museum of Crime & Punishment.

2.^ "Chase's Calendar of Events 2007", p. 291

3.^ Scurr, pp. 222-223

4.^ Abbot, p. 144

5.^ Sanson, p. 406

6.^ Bernard, p. 150F

7.^ Goncourt, p. 432

8.^ Fleischamnn, p. 46f

9.^ Tuetey, p. 551

10.^ Hatin, p. 53f

11.^ Seligman, p. 401

12.^ Lenotre, p.234

13.^ Seligman, p. 463

14.^ Scurr, p. 222

15.^ Abbott, p. 144

16.^ Scurr, p. 223

The Yellow Handkerchief is an independent drama film. Set in the present-day South, The Yellow Handkerchief stars William Hurt as Brett, an ex-convict who embarks on a road trip with two troubled teens, Martine (Kristen Stewart) and Gordy (Eddie Redmayne) through post-Hurricane Katrina Louisiana in an attempt to reach his ex-wife and long lost love, May (Maria Bello). Along the way, the three reflect on their existence, struggle for acceptance, and find their way not only through Louisiana, but through life. Directed by Udayan Prasad and produced by Arthur Cohn, It is scheduled for a limited release on February 26, 2010 by Samuel Goldwyn Films.

Plot

After being released from prison after six years, ex-convict Brett Hanson (William Hurt) becomes lost in a new and unfamiliar world of freedoms and responsibilities. Struggling to reconcile himself with his disastrous past, he embarks on a journey to his home of Southern Louisiana to reunite with the ex-wife he left behind, May (Maria Bello). Along this journey, he meets two teenagers: Martine (Kristen Stewart), a troubled 15-year-old who has just escaped her family, and Gordy (Eddie Redmayne), a geeky outcast desperately seeking acceptance. Martine and Gordy offer to give Brett a lift home, and the three embark on a road trip through post-Hurricane Katrina Louisiana, reflecting on their own personal misfit status while discovering in themselves and each other the acceptance each so deeply desires. Brett weighs whether to start a new life or rekindle his love with May, Martine reevaluates her relationships with boys and her family, and Gordy struggles with his affection for Martine.

The film is loosely based on a short story by writer Pete Hamill.

Linda Susan Boreman (January 10, 1949 – April 22, 2002), better known by her stage name "Linda Lovelace," was a porn actress who was famous for her performance of deep throat fellatio in the enormously successful 1972 hardcore porn film Deep Throat. She later denounced her pornography career, claimed that she had been forced into it by her sadistic first husband, and for a while became a spokeswoman for the anti-pornography movement.

Boreman contracted hepatitis from the blood transfusion she received after her 1970 car accident. She underwent a liver transplant in 1987. In 1996, Boreman divorced Larry Marchiano. In 2000, she was featured on the E! Entertainment Network's E! True Hollywood Story. The following year, she did a pictorial as Linda Lovelace for the magazine Leg Show. She said she did not object to this, because "there's nothing wrong with looking sexy as long as it's done with taste."

On April 3, 2002, Boreman lost control of her car, which rolled twice. She suffered massive trauma and internal injuries. On April 22, 2002 she was taken off life support and died in Denver, Colorado at the age of 53. Her ex-husband, Larry Marchiano, and their two children were present when she died. Boreman was interred at Parker Cemetery in Parker, Colorado.

Abraham "Bram" Stoker (8 November 1847 – 20 April 1912) was an Irish novelist and short story writer, best known today for his 1897 Gothic novel Dracula. During his lifetime, he was better known as the personal assistant of actor Henry Irving and business manager of the Lyceum Theatre in London, which Irving owned.

Early life

Stoker was born in 1847 at 15 Marino Crescent, Clontarf.[1][2] His parents were Abraham Stoker (1799–1876), from Dublin, and the feminist Charlotte Mathilda Blake Thornley (1818–1901), who came from Ballyshannon, County Donegal. Stoker was the third of seven children.[3] Abraham and Charlotte were members of the Church of Ireland Parish of Clontarf and attended the parish church with their children, who were baptised there.

Stoker was bed-ridden until he started school at the age of seven, when he made a complete recovery. Of this time, Stoker wrote, "I was naturally thoughtful, and the leisure of long illness gave opportunity for many thoughts which were fruitful according to their kind in later years." He was educated in a private school run by the Rev. William Woods.[4]

After his recovery, he grew up without further major health issues, even excelling as an athlete (he was named University Athlete) at Trinity College, Dublin, which he attended from 1864 to 1870. He graduated with honours in mathematics. He was auditor of the College Historical Society and president of the University Philosophical Society, where his first paper was on "Sensationalism in Fiction and Society".

Early career

While still a student he became interested in the theatre. Through the influence of a friend, Dr. Maunsell, he became the theatre critic for a newspaper, the Dublin Evening Mail, co-owned by the author of Gothic tales Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu. At a time when theatre critics were held in low esteem, he attracted notice by the quality of his reviews. In December 1876 he gave a favourable review of the actor Henry Irving's performance as Hamlet at the Theatre Royal in Dublin. Irving read the review and invited Stoker for dinner at the Shelbourne Hotel, where he was staying. After that they became friends. Stoker also wrote stories, and in 1872 "The Crystal Cup" was published by the London Society, followed by "The Chain of Destiny" in four parts in The Shamrock. In 1876, while employed as a civil servant in Dublin, Stoker wrote a non-fiction book (The Duties of Clerks of Petty Sessions in Ireland, published 1879), which long remained a standard work on the subject.[4]

In 1878 Stoker married Florence Balcombe, daughter of Lieutenant-Colonel James Balcombe of 1 Marino Crescent, a celebrated beauty whose former suitor was Oscar Wilde[5]. Stoker had known Wilde from his student days, having proposed him for membership of the university’s Philosophical Society while he was president. Wilde was upset at Florence's decision, but Stoker later resumed the acquaintanceship, and after Wilde's fall visited him on the Continent.[6]

The Stokers moved to London, where Stoker became acting-manager and then business manager of Irving's Lyceum Theatre, London, a post he held for 27 years. On 31 December 1879, Bram and Florence's only child was born, a son whom they christened Irving Noel Thornley Stoker. The collaboration with Irving was very important for Stoker and through him he became involved in London's high society, where he met, among other notables, James Abbott McNeill Whistler and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (to whom he was distantly related). Working for Irving, the most famous actor of his time, and managing one of the most successful theatres in London made Stoker a notable if very busy man. He was absolutely dedicated to Irving and his memoirs of Irving show how he idolised him. In London Stoker also met Hall Caine who became one of his closest friends - he dedicated Dracula to him.

In the course of Irving's tours, Stoker got the chance to travel around the world, although he never visited Eastern Europe, a setting for his most famous novel. Stoker particularly enjoyed visits to the United States, where Irving was popular. With Irving he was invited twice to the White House, and knew both William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt. Stoker was a great admirer of the country, setting two of his novels there and using Americans as characters, the most notable being Quincey Morris. He also got a chance to meet one of his literary idols Walt Whitman.

Writings

While working as manager for actor Henry Irving, and as secretary and director of London's Lyceum Theatre, he began writing novels beginning with The Snake's Pass in 1890 and Dracula in 1897. During this period, Stoker was also part of the literary staff of the London Telegraph newspaper and wrote other works of fiction, including the horror novels The Lady of the Shroud (1909) and The Lair of the White Worm (1911).[7] In 1906, after Irving's death, he published his life of Irving, which proved very successful[4] and managed productions at the Prince of Wales Theatre.

Before writing Dracula, Stoker spent several years researching European folklore and mythological stories of vampires. Dracula is an epistolary novel, written as a collection of realistic, but completely fictional, diary entries, telegrams, letters, ship's logs, and newspaper clippings, all of which added a level of detailed realism to his story, a skill he developed as a newspaper writer. At the time of its publication, it was considered a "straightforward horror novel" based on imaginary creations of supernatural life.[7] "It gave form to a universal fantasy . . . and became a part of popular culture."[7]

According to the Encyclopedia of World Biography, Stoker's stories are today included within the categories of "horror fiction," "romanticized Gothic" stories, and "melodrama."[7] They are classified alongside other "works of popular fiction" such as Shelley's Frankenstein[8]:394 which, according to historian Jules Zanger, also used the "myth-making" and story-telling method of having "multiple narrators" telling the same tale from different perspectives. "'They can't all be lying,' thinks the reader."[9]

The original 541-page manuscript of Dracula, believed to have been lost, was found in a barn in northwestern Pennsylvania during the early 1980s.[10] It included the typed manuscript with many corrections, and handwritten on the title page was "THE UN-DEAD." The author's name was shown at the bottom as Bram Stoker. Author Robert Latham notes, "the most famous horror novel ever published, its title changed at the last minute."[8]

Stoker's inspirations for the story, in addition to Whitby, may have included a visit to Slains Castle in Aberdeenshire, a visit to the crypts of St. Michan's Church in Dublin and the novella Carmilla by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu.[11]

Death

After suffering a number of strokes Bram Stoker died at No 26 St George's Square in 1912.[12] Some biographers attribute the cause of death to tertiary syphilis[13]. He was cremated and his ashes placed in a display urn at Golders Green Crematorium. After Irving Noel Stoker's death in 1961, his ashes were added to that urn. The original plan had been to keep his parents' ashes together, but after Florence Stoker's death her ashes were scattered at the Gardens of Rest. To visit his remains at Golders Green, visitors must be escorted to the room the urn is housed in, for fear of vandalism.

Beliefs and philosophy

Stoker was brought up as a Protestant, in the Church of Ireland. He was a strong supporter of the Liberal party. He took a keen interest in Irish affairs[4] and was what he called a "philosophical Home Ruler", believing in Home Rule for Ireland brought about by peaceful means - but as an ardent monarchist he believed that Ireland should remain within the British Empire which he believed was a force for good. He was a great admirer of Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone whom he knew personally, and admired his plans for Ireland[14].

Stoker had a strong interest in science and medicine and a belief in progress. Some of his novels like The Lady of the Shroud (1909) can be seen as early science fiction. Like many people of his time Stoker believed in the concept of scientific racism drawing on his belief in Phrenology and these fears form elements in novels like Dracula.[citation needed] This is also reflected in his interest in early theories of criminology - he read both Cesare Lombroso and Max Nordau and used them in Dracula.

Stoker had an interest in the occult especially mesmerism, but was also wary of occult fraud and believed strongly that superstition should be replaced by more scientific ideas. In the mid 1890s, Stoker is rumoured to have become a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, though there is no concrete evidence to support this claim.[15][16] One of Stoker's closest friends was J.W. Brodie-Innis, a major figure in the Order, and Stoker himself hired Pamela Coleman Smith, as an artist at the Lyceum Theater.

Posthumous

The short story collection Dracula's Guest and Other Weird Stories was published in 1914 by Stoker's widow Florence Stoker. The first film adaptation of Dracula was released in 1922 and was named Nosferatu. It was directed by Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau and starred Max Schreck as Count Orlock. Nosferatu was produced while Florence Stoker, Bram Stoker's widow and literary executrix, was still alive. Represented by the attorneys of the British Incorporated Society of Authors, she eventually sued the filmmakers. Her chief legal complaint was that she had been neither asked for permission for the adaptation nor paid any royalty. The case dragged on for some years, with Mrs. Stoker demanding the destruction of the negative and all prints of the film. The suit was finally resolved in the widow's favour in July 1925. Some copies of the film survived, however and the film has become well known. The first authorized film version of Dracula did not come about until almost a decade later when Universal Studios released Tod Browning's Dracula starring Bela Lugosi.

Because of the Stokers' frustrating history with Dracula's copyright, a great-grandnephew of Bram Stoker, Canadian writer Dacre Stoker, with encouragement from screenwriter Ian Holt, decided to write "a sequel that bore the Stoker name" to "reestabish creative control over" the original novel. In 2009, Dracula: The Un-Dead was released, written by Dacre Stoker and Ian Holt. Both writers "based [their work] on Bram Stoker's own handwritten notes for characters and plot threads excised from the original edition" along with their own research for the sequel. This also marked Dacre Stoker's writing debut.[17][18]

Bibliography

Novels

The Snake's Pass (1890)

The Watter's Mou' (1895)

The Shoulder of Shasta (1895)

Dracula (1897)

Miss Betty (1898)

The Mystery of the Sea (1902)

The Jewel of Seven Stars (1903)

The Man (aka: The Gates of Life) (1905)

Lady Athlyne (1908)

The Lady of the Shroud (1909)

The Lair of the White Worm (aka: The Garden of Evil) (1911)

Short story collections

Under the Sunset (1881), comprising eight fairy tales for children.

Snowbound: The Record of a Theatrical Touring Party (1908)

Dracula's Guest and Other Weird Stories (1914), published posthumously by Florence Stoker

Uncollected stories

"The Bridal of Death" (alternate ending to The Jewel of Seven Stars)

"Buried Treasures"

"The Chain of Destiny"

"The Crystal Cup"

"The Dualitists; or, The Death Doom of the Double Born"

"Lord Castleton Explains" (chapter 10 of The Fate of Fenella)

"The Gombeen Man" (chapter 3 of The Snake's Pass)

"In the Valley of the Shadow"

"The Man from Shorrox"

"Midnight Tales"

"The Red Stockade"

"The Seer" (chapters 1 and 2 of The Mystery of the Sea)

Non-fiction

The Duties of Clerks of Petty Sessions in Ireland (1879)

A Glimpse of America (1886)

Personal Reminiscences of Henry Irving (1906)

Famous Impostors (1910)

Bram Stoker's Notes for Dracula: A Facsimile Edition (2008) Bram Stoker Annotated and Transcribed by Robert Eighteen-Bisang and Elizabeth Miller, Foreword by Michael Barsanti. Jefferson NC & London: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-3410-7

Critical Works on Stoker

William Hughes, Beyond Dracula (Palgrave, 2000) ISBN 0312231369 [19]

References and notes

1.^ Belford, Barbara (2002). Bram Stoker and the Man Who Was Dracula. Cambridge, Mass.: Da Capo Press. p. 17. ISBN 0-306-81098-0.

2.^ Note, as location has led to multiple edits: The location was, and is, in the Civil Parish of Clontarf. Clontarf extends to the east side of the Malahide Road and borders Marino. Fairview is further west commencing just after Marino Mart.

3.^ His siblings were: Sir (William) Thornley Stoker, born in 1845; Mathilda, born 1846; Thomas, born 1850; Richard, born 1852; Margaret, born 1854; and George, born 1855

4.^ Obituary, Irish Times, 23 April 1912

5.^ Irish Times, 8 March 1882, page 5

6.^ "Why Dracula never loses his bite". Irish Times. last modified 2009. http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/weekend/2009/0328/1224243595688.html. Retrieved 2009-01-04.

7.^ Encyclopedia of World Biography, Gale Research (1998) vol 8. pgs. 461-464

8.^ Latham, Robert. Science Fiction & Fantasy Book Review Annual, Greenwood Publishing (1988) p. 67

9.^ Zanger, Jules. Blood Read: The Vampire as Metaphor in Contemporary Culture ed. Joan Gordon. Univ. of Pennsylvania Press (1997), pgs. 17-24

10.^ http://online.wsj.com/article/SB122514491757273633.html

11.^ Boylan, Henry (1998). A Dictionary of Irish Biography, 3rd Edition. Dublin: Gill and MacMillan. p. 412. ISBN 0-7171-2945-4.

12.^ "Bram Stoker". Victorian Web. last modified 1998. http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/stoker/bio.html. Retrieved 2008-12-12.

13.^ Gibson, Peter (1985). The Capital Companion. Webb & Bower. pp. 365–366. ISBN 0863500420.

14.^ Murray, Paul. From the Shadow of Dracula: A Life of Bram Stoker. 2004.

15.^ Ravenscroft, Trevor (1982). The occult power behind the spear which pierced the side of Christ. Red Wheel. pp. p165. ISBN 0877285470.

16.^ Picknett, Lynn (2004). The Templar Revelation: Secret Guardians of the True Identity of Christ. Simon and Schuster. pp. p201. ISBN 0743273257.

17.^ Dracula: The Un-Dead by Dacre Stoker and Ian Holt

18.'^ Dracula: The Undeads overview

19.^ http://muse.jhu.edu/login?uri=/journals/victorian_studies/v044/44.2glover.html

The Runaways is a 2010 American musical/biographical drama film, based on the 1970s all-girl rock band of the same name. The film is written and directed by Floria Sigismondi, with Joan Jett as one of the film's executive producers, and stars Kristen Stewart as Joan Jett, Dakota Fanning as Cherie Currie, Stella Maeve as Sandy West, Scout Taylor-Compton as Lita Ford, and Michael Shannon as Kim Fowley. Alia Shawkat plays the band's bassist, a fictional character named Robin, created as a result of legal issues preventing the portrayal of bassist Jackie Fox.

The film is based on Cherie Currie's memoir, Neon Angel: A Memoir of a Runaway.

Plot

The Runaways follows two friends, Joan (Kristen Stewart) and Cherie (Dakota Fanning), as they rise from rebellious L.A. street kids to rock stars of the now legendary group that paved the way for future generations of girl bands. They fall under the Svengali-like influence of rock impresario, Kim Fowley (Michael Shannon), who turns the group into an outrageous success and a family of misfits. With its tough-chick image and raw talent, the band quickly earns a name for itself - and so do its two leads: Joan is the band’s pure rock’ n’ roll heart, while Cherie, with her Bowie-Bardot looks, is the sex kitten.

Gustave Moreau (6 April 1826 – 18 April 1898) was a French Symbolist painter whose main focus was the illustration of biblical and mythological figures. As a painter of literary ideas rather than visual images, Moreau appealed to the imaginations of some Symbolist writers and artists, who saw him as a precursor to their movement.

Biography

Moreau was born in Paris. His father, Louis Jean Marie Moreau, was an architect, who recognized his talent. His mother was Adele Pauline des Moutiers. Moreau studied under François-Édouard Picot and became a friend of Théodore Chassériau, whose work strongly influenced his own. Moreau carried on a deeply personal 25-year relationship, possibly romantic, with Adelaide-Alexandrine Dureux, a woman whom he drew several times. His first painting was a Pietà which is now located in the cathedral at Angoulême. He showed A Scene from the Song of Songs and The Death of Darius in the Salon of 1853. In 1853 he contributed Athenians with the Minotaur and Moses Putting Off his Sandals within Sight of the Promised Land to the Great Exhibition.

Oedipus and the Sphinx, one of his first symbolist paintings, was exhibited at the Salon of 1864. Over his lifetime, he produced over 8,000 paintings, watercolors and drawings, many of which are on display in Paris' Musée national Gustave Moreau at 14, rue de la Rochefoucauld (IXe arrondissement). The museum is in his former workshop, and was opened to the public in 1903. André Breton famously used to "haunt" the museum and regarded Moreau as a precursor to Surrealism.

He had become a professor at Paris' École des Beaux-Arts in 1891 and counted among his many students the fauvist painters, Henri Matisse and Georges Rouault.

Moreau died in Paris and was buried there in the Cimetière de Montmartre.

Twilight is a series of four vampire-based fantasy romance novels by American author Stephenie Meyer. It charts a period in the life of Isabella "Bella" Swan, a teenage girl who moves to Forks, Washington, and falls in love with a 104-year-old vampire named Edward Cullen. The series is told primarily from Bella's point of view, with the epilogue of Eclipse and Part II of Breaking Dawn being told from the viewpoint of character Jacob Black, a werewolf. The unpublished Midnight Sun is a retelling of the first book, Twilight, from Edward Cullen's point of view.Since the release of the first novel, Twilight, in 2005, the books have gained immense popularity and commercial success around the world. The series is most popular among young adults; the four books have won multiple awards, most notably the 2008 British Book Award for "Children's Book of the Year" for Breaking Dawn, while the series as a whole won the 2009 Kids' Choice Award for Favorite Book.As of November 2009, the series has sold over 85 million copies worldwide with translations into at least 38 different languages around the globe. The four Twilight books have consecutively set records as the biggest selling novels of 2008 on the USA Today Best-Selling Books list and have spent over 235 weeks on the New York Times Best Seller list for Children's Series Books.Thus far, the first three books are being made into a series of motion pictures by Summit Entertainment; the film adaptation of Twilight was released in 2008 and the second, The Twilight Saga: New Moon, was released on November 20, 2009. The third film, The Twilight Saga: Eclipse, is set to be released June 30, 2010.

The Twilight Saga: Eclipse is an upcoming romantic-fantasy film scheduled for release on June 30, 2010. It is based on Stephenie Meyer's Eclipse and will be the third installment of The Twilight Saga film series, following 2008's Twilight and 2009's New Moon. Summit Entertainment greenlit the film in February 2009. Directed by David Slade, the film will star Kristen Stewart, Robert Pattinson, and Taylor Lautner, reprising their roles as Bella Swan, Edward Cullen, and Jacob Black, respectively. Melissa Rosenberg will be returning as screenwriter. Rachelle Lefevre, who played Victoria in the previous two installments, will not be returning due to scheduling conflicts; instead, Bryce Dallas Howard will play Victoria. It will be the first Twilight film to be released in IMAX.

Summit Entertainment released a plot summary of The Twilight Saga: Eclipse on February 20, 2009, which states:

"As Seattle is ravaged by a string of mysterious killings and a malicious vampire continues her quest for revenge, Bella once again finds herself surrounded by danger. In the midst of it all, she is forced to choose between her love for Edward and her friendship with Jacob — knowing that her decision has the potential to ignite the ageless struggle between vampire and werewolf. With her graduation quickly approaching, Bella has one more decision to make: life or death."

Edward St. John Gorey (ca. February 22, 1925 – April 15, 2000) was an American writer and artist noted for his macabre illustrated books.[1]

Early life

Edward St. John Gorey was born in Chicago. His parents, Helen Dunham Garvey and Edward Lee Gorey,[2] divorced in 1936 when he was 11, then remarried in 1952 when he was 27. One of his stepmothers was Corinna Mura (1909-65), a cabaret singer who had a small role in the classic film Casablanca as the woman playing the guitar while singing "La Marseillaise" at Rick's Café Américain. His father was briefly a journalist. Gorey's maternal great-grandmother, Helen St. John Garvey, was a popular 19th century greeting card writer and artist, from whom he claimed to have inherited his talents.

Gorey attended a variety of local grade schools and then the Francis W. Parker School. He spent 1944 to 1946 in the Army at Dugway Proving Ground in Utah, and then attended Harvard University from 1946 to 1950, where he studied French and roomed with poet Frank O'Hara.

Although he would frequently state that his formal art training was "negligible," Gorey studied art for one semester at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1943, eventually becoming a professional illustrator.

Career

From 1953 to 1960, he lived in New York City and worked for the Art Department of Doubleday Anchor, illustrating book covers and in some cases adding illustrations to the text. He illustrated works as diverse as Dracula by Bram Stoker, The War of the Worlds by H. G. Wells, and Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats by T. S. Eliot. In later years he produced cover illustrations and interior artwork for many children's books by John Bellairs, as well as books begun by Bellairs and continued by Brad Strickland after Bellairs' death.

His first independent work, The Unstrung Harp, was published in 1953. He also published under pen names that were anagrams of his first and last names, such as Ogdred Weary, Dogear Wryde, Ms. Regera Dowdy, and dozens more. His books also feature the names Eduard Blutig ("Edward Gory"), a German language pun on his own name, and O. Müde (German for O. Weary).

The New York Times credits bookstore owner Andreas Brown and his store, the Gotham Book Mart, with launching Gorey's career: "it became the central clearing house for Mr. Gorey, presenting exhibitions of his work in the store's gallery and eventually turning him into an international celebrity." [3]

Gorey's illustrated (and sometimes wordless) books, with their vaguely ominous air and ostensibly Victorian and Edwardian settings, have long had a cult following. Gorey became particularly well-known through his animated introduction to the PBS series Mystery! in 1980, as well as his designs for the 1977 Broadway production of Dracula, for which he won a Tony Award for Best Costume Design. (He was also nominated for Best Scenic Design.)

Edward Gorey's home on Cape Cod (2006).Because of the settings and style of Gorey's work, many people have assumed he was British; in fact, he never visited Britain, and he almost never traveled. In later years, he lived year-round in Yarmouth Port, Massachusetts, on Cape Cod, where he wrote and directed numerous evening-length entertainments, often featuring his own papier-mâché puppets, in an ensemble known as La Theatricule Stoique. His major theatrical work was the libretto for an Opera Seria for Hand Puppets titled The White Canoe, with a score by the composer Daniel James Wolf. Based on the Lady of the Lake legend, the opera premiered posthumously. On August 13, 1987, his play Lost Shoelaces premiered in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. In the early 1970s, Gorey wrote an unproduced screenplay for a silent film, The Black Doll.

Gorey was noted for his fondness for ballet (for many years, he religiously attended all performances of the New York City Ballet), fur coats, tennis shoes, and cats, of which he had many. All figure prominently in his work. His knowledge of literature and films was unusually extensive, and in his interviews, he named Jane Austen, Agatha Christie, Francis Bacon, George Balanchine, Balthus, Louis Feuillade, Ronald Firbank, Lady Murasaki Shikibu, Robert Musil, Yasujiro Ozu, Anthony Trollope, and Johannes Vermeer as some of his favorite artists. Gorey was also an unashamed pop-culture junkie, avidly following soap operas and TV comedies like Petticoat Junction and Cheers, and he had particular affection for dark genre series like Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Batman: The Animated Series, and The X-Files; he once told an interviewer that he so enjoyed the Batman series that it was influencing the visual style of one of his upcoming books. Gorey treated TV commercials as an artform in themselves, even taping his favorites for later study. Gorey was especially fond of movies, and for a time he wrote regular reviews for the Soho Weekly under the pseudonym Wardore Edgy.

Personal life

Although Gorey's books were popular with children, he did not associate with children much and had no particular fondness for them. Gorey never married, professed to have little interest in romance, and never discussed any specific romantic relationships in interviews. In the book The Strange Case of Edward Gorey, published after Gorey's death, his friend Alexander Theroux reported that when Gorey was pressed on the matter of his sexual orientation, he said that even he was not sure whether he was gay or straight. When asked what his sexual preferences were in an interview, he said,

“I'm neither one thing nor the other particularly. I am fortunate in that I am apparently reasonably undersexed or something...I've never said that I was gay and I've never said that I wasn't...what I'm trying to say is that I am a person before I am anything else.... ”

Edward Gorey agreed in an interview that the "sexlessness" of his novels were a product of his asexuality[4].

From 1996 to his death in April 2000, the normally reclusive artist was the subject of a direct cinema-style documentary directed by Christopher Seufert. This was not yet released as of 2010. He was interviewed on Tribute To Edward Gorey, an hour long community cable television show produced by artist and friend Joyce Kenney. He contributed his videos and personal thoughts. Edward served as judge in Yarmouth art shows and enjoyed activities at the local cable station, studying computer art and serving as cameraman on many Yarmouth shows. His Cape Cod house is called Elephant House and is the subject of a photography book titled Elephant House: Or, the Home of Edward Gorey, with photographs and text by Kevin McDermott. The house is now the Edward Gorey House Museum.[5]

Legacy

In 1999, Edward Gorey designed the front and rear cover art for his long time friend Clif Hanger, the founder-lyricist-vocalist for the Cape Cod, Massachusetts-based punk rock band The Freeze. The album, titled One False Move, was released in late 1999. Gorey also co-wrote with Clif Hanger the lyrics to the band's song "Alien Heads."

Gorey has become an iconic figure in the Goth subculture. Events themed on his works and decorated in his characteristic style are common in the more Victorian-styled elements of the subculture, notably the costumed Edwardian costume balls held annually in San Francisco and Los Angeles, which include performances based on his works. The "Edwardian" in this case refers less to the Edwardian period of history than to Gorey himself, whose characters are depicted as wearing fashion styles ranging from those of the mid-19th century to the 1930s.

Director Mark Romanek's music video for the Nine Inch Nails song "The Perfect Drug" was designed specifically to look like a Gorey book, with familiar Gorey elements including oversized urns, topiary plants, and glum, pale characters in full Edwardian costume.[6] Also, Caitlín R. Kiernan has published a short story titled "A Story for Edward Gorey" (Tales of Pain and Wonder, 2000), which features Gorey's black doll.

A more direct link to Gorey's influence on the music world is evident in The Gorey End,[7] an album recorded in 2003 by the Tiger Lillies and the Kronos Quartet. This album was a collaboration with Gorey, who liked previous work by The Tiger Lillies so much that he sent them a large box of his unpublished work, which were then adapted and turned into songs. Gorey died before hearing the finished album.

In 1976 jazz composer Michael Mantler recorded an album called The Hapless Child (Watt/ECM) with Robert Wyatt, Terje Rypdal, Carla Bley and Jack DeJohnette. It contains musical adaptations of The Sinking Spell, The Object Lesson, The Insect God, The Doubtful Guest, The Remembered Visit and The Hapless Child. The three last songs have also been published on his 1987 Live album with Jack Bruce, Rick Fenn and Nick Mason.

There is a reference to Gorey in Andrew Bird's song "Measuring Cups," from his album The Mysterious Production of Eggs.

The Perry Bible Fellowship Web comic featured a strip called "The Throbblefoot Aquarium" which features Gorey-esque illustrations with a small note reading "apologies, Edward Gorey."

The opening titles of the PBS series Mystery! is based on Gorey's art, in an animated sequence co-directed by Derek Lamb.

In the last few decades of his life, Gorey merchandise became quite popular, with stuffed dolls, cups, stickers, posters, and other items available at malls around the United States.

The Jim Henson Company announced plans to produce a feature film based on The Doubtful Guest to be directed by Brad Peyton. The release date is unknown. There has not been much information since the announcement in 2007.

Style

Gorey is typically described as an illustrator. His books can be found in the humor and cartoon sections of major bookstores, but books like The Object Lesson have earned serious critical respect as works of surrealist art. His experimentations — creating books that were wordless, books that were literally matchbox-sized, pop-up books, books entirely populated by inanimate objects — complicates matters still further. As Gorey told Richard Dyer of The Boston Globe, "Ideally, if anything [was] any good, it would be indescribable." Gorey classified his own work as literary nonsense, the genre made most famous by Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear.

In response to being called gothic, he stated, "If you're doing nonsense it has to be rather awful, because there'd be no point. I'm trying to think if there's sunny nonsense. Sunny, funny nonsense for children — oh, how boring, boring, boring. As Schubert said, there is no happy music. And that's true, there really isn't. And there's probably no happy nonsense, either."[8]

Bibliography

Gorey wrote more than 100 books, including:

The Unstrung Harp, Brown and Company, 1953

The Listing Attic, Brown and Company, 1954

The Doubtful Guest, Doubleday, 1957

The Object Lesson, Doubleday, 1958

The Bug Book, Looking Glass Library, 1959

The Fatal Lozenge: An Alphabet, Obolensky, 1960

The Curious Sofa: A Pornographic Tale by Ogdred Weary, Astor-Honor, 1961

The Hapless Child, Obolensky, 1961

The Willowdale Handcar: Or, the Return of the Black Doll, Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1962

The Beastly Baby, Fantod Press, 1962

The Vinegar Works: Three Volumes of Moral Instruction, Simon and Schuster, 1963

The Gashlycrumb Tinies

The Insect God

The West Wing

The Wuggly Ump, Lippincott, 1963

The Nursery Frieze, Fantod Press, 1964

The Sinking Spell, Obolensky, 1964

The Remembered Visit: A Story Taken From Life, Simon and Schuster, 1965

Three Books From Fantod Press (1), Fantod Press, 1966

The Evil Garden

The Inanimate Tragedy

The Pious Infant

The Gilded Bat, Cape, 1967

The Utter Zoo, Meredith Press, 1967

The Other Statue, Simon and Schuster, 1968

The Blue Aspic, Meredith Press, 1968

The Epiplectic Bicycle, Dodd and Mead, 1969

The Iron Tonic: Or, A Winter Afternoon in Lonely Valley, Albondocani Press, 1969

Three Books From The Fantod Press (2), Fantod Press, 1970

The Chinese Obelisks: Fourth Alphabet

Donald Has A Difficulty

The Osbick Bird

The Sopping Thursday, Gotham Book Mart, 1970

Three Books From The Fantod Press (3), Fantod Press, 1971

The Deranged Cousins

The Eleventh Episode

The Untitled Book

The Awdrey-Gore Legacy, 1972

Leaves From A Mislaid Album, Gotham Book Mart, 1972

The Abandoned Sock, Fantod Press, 1972

A Limerick, Salt-Works Press, 1973

The Lost Lions, Fantod Press, 1973

The Green Beads, Albondocani Press, 1978

The Glorious Nosebleed: Fifth Alphabet, Mead, 1975

The Grand Passion: A Novel, Fantod Press, 1976

The Broken Spoke, Mead, 1976

The Loathsome Couple, Mead, 1977

Dancing Cats And Neglected Murderesses, Workman, 1980

The Water Flowers, Congdon & Weed, 1982

The Dwindling Party, Random House, 1982

The Prune People, Albondocani Press, 1983

Gorey Stories, 1983

The Tunnel Calamity, Putnam's Sons, 1984

The Eclectic Abecedarium, Adama Books, 1985

The Prune People II, Albondocani Press, 1985

The Improvable Landscape, Albondocani Press, 1986

The Raging Tide: Or, The Black Doll's Imbroglio, Beaufort Books, 1987

Q. R. V. (later retitled The Universal Solvent), Anne & David Bromer, 1989

The Stupid Joke, Fantod Press, 1990

The Fraught Settee, Fantod Press, 1990

The Doleful Domesticity; Another Novel, Fantod Press, 1991

The Retrieved Locket, Fantod Press, 1994

The Unknown Vegetable, Fantod Press, 1995

The Just Dessert: Thoughtful Alphabet XI, Fantod Press, 1997

Deadly Blotter: Thoughtful Alphabet XVII, Fantod Press, 1997

The Haunted Tea-Cosy: A Dispirited and Distasteful Diversion for Christmas, Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1998

The Headless Bust: A Melancholy Meditation on the False Millennium, Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1999

The Gashlycrumb Tinies (1963).Many of Gorey's works were published obscurely and are difficult to find (and priced accordingly). However, the following four omnibus editions collect much of his material. Because his original books are rather short, these editions may contain 15 or more in each volume.

Amphigorey, 1972 (ISBN 0-399-50433-8) - contains The Unstrung Harp, The Listing Attic, The Doubtful Guest, The Object-Lesson, The Bug Book, The Fatal Lozenge, The Hapless Child, The Curious Sofa, The Willowdale Handcar, The Gashlycrumb Tinies, The Insect God, The West Wing, The Wuggly Ump, The Sinking Spell, and The Remembered Visit

Amphigorey Too, 1975 (ISBN 0-399-50420-6) - contains The Beastly Baby, The Nursery Frieze, The Pious Infant, The Evil Garden, The Inanimate Tragedy, The Gilded Bat, The Iron Tonic, The Osbick Bird, The Chinese Obelisks (bis), The Deranged Cousins, The Eleventh Episode, [The Untitled Book], The Lavender Leotard, The Disrespectful Summons, The Abandoned Sock, The Lost Lions, Story for Sara [by Alphonse Allais], The Salt Herring [by Charles Cros], Leaves from a Mislaid Album, and A Limerick

Amphigorey Also, 1983 (ISBN 0-15-605672-0) - contains The Utter Zoo, The Blue Aspic, The Epiplectic Bicycle, The Sopping Thursday, The Grand Passion, Les Passementeries Horribles, The Eclectic Abecedarium, L'Heure bleue, The Broken Spoke, The Awdrey-Gore Legacy, The Glorious Nosebleed, The Loathsome Couple, The Green Beads, Les Urnes Utiles, The Stupid Joke, The Prune People, and The Tuning Fork

Amphigorey Again, 2006 (ISBN 0-15-101107-9) - contains The Galoshes of Remorse, Signs of Spring, Seasonal Confusion, Random Walk, Category, The Other Statue, 10 Impossible Objects (abridged), The Universal Solvent (abridged), Scenes de Ballet, Verse Advice, The Deadly Blotter, Creativity, The Retrieved Locket, The Water Flowers, The Haunted Tea-Cosy, Christmas Wrap-Up, The Headless Bust, The Just Dessert, The Admonitory Hippopotamus, Neglected Murderesses, Tragedies Topiares, The Raging Tide, The Unknown Vegetable, Another Random Walk, Serious Life: A Cruise, Figbash Acrobate, La Malle Saignante, and The Izzard Book

He also illustrated more than 50 works by other authors, including Samuel Beckett, Edward Lear, John Bellairs, H. G. Wells, Alain-Fournier, Charles Dickens, T. S. Eliot, Hilaire Belloc, Muriel Spark, Florence Parry Heide, and John Ciardi.

Pseudonyms

Gorey was very fond of word games, particularly anagrams. He wrote many of his books under pseudonyms that were usually anagrams of his own name (most famously Ogdred Weary). Some of these are listed below, with the corresponding book title(s). Eduard Blutig is also a word game: "Blutig" is German (the language from which these two books were purportedly translated) for "bloody," which is a synonym for "gory."

Ogdred Weary - The Curious Sofa, The Beastly Baby

Mrs. Regera Dowdy - The Pious Infant

Eduard Blutig - The Evil Garden (translated from Der Böse Garten by Mrs. Regera Dowdy), The Tuning Fork (translated from Der Zeitirrthum by Mrs. Regera Dowdy)

Raddory Gewe - The Eleventh Episode

Dogear Wryde - The Broken Spoke/Cycling Cards

E. G. Deadworry - The Awdrey-Gore Legacy

D. Awdrey-Gore - The Toastrack Enigma, The Blancmange Tragedy, The Postcard Mystery, The Pincushion Affair, The Toothpaste Murder, The Dustwrapper Secret (Note: These books, although attributed to Awdrey-Gore in Gorey's book The Awdrey-Gore Legacy, were not really written.)

Edward Pig - The Untitled Book

Wardore Edgy

Madame Groeda Weyrd - The Fantod Deck

Footnotes

1.^ Kelley, Tina (April 16 2000), "Edward Gorey, Eerie Illustrator And Writer, 75", The New York Times, http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C05E1D81731F935A25757C0A9669C8B63&sec=&spon=&partner=permalink&exprod=permalink

2.^ Ancestry of Edward Gorey

3.^ Gussow, Mel (April 17 2000), "Edward Gorey, Artist and Author Who Turned the Macabre Into a Career, Dies at 75", The New York Times, http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9500E1DE1431F934A25757C0A9669C8B63&sec=&spon=&partner=permalink&exprod=permalink

4.^ Gorey, Edward (2002). Ascending Peculiarity: Edward Gorey on Edward Gorey. Harvest Books. ISBN 978-0156012911.

5.^ McDermott, Kevin. Elephant House: Or, the Home of Edward Gorey. Pomegranate Communications (2003). ISBN 0764924958 and ISBN 978-0764924958

6.^ Interview with Mark Romanek, in the currently unreleased documentary by Christopher Seufert.

7.^ The Tiger Lillies' webpage for this album; EMI 7243 5 57513 2 4

8.^ Schiff, Stephen. “Edward Gorey and the Tao of Nonsense.” The New Yorker, November 9, 1992: 84-94, p. 89.